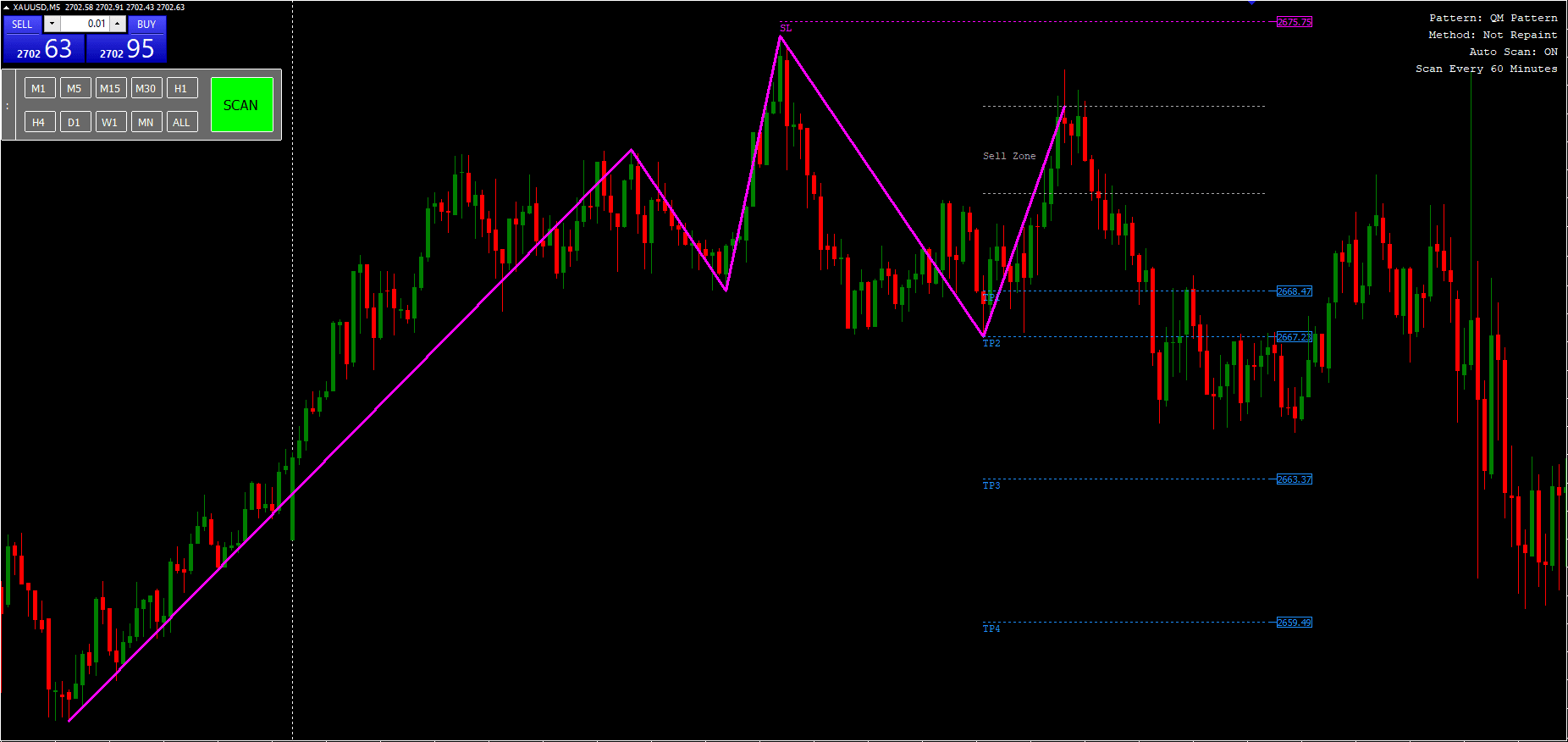

The Quasimodo pattern is a fascinating reversal trading pattern that traders watch for at the end of an uptrend. It’s a unique price formation that consists of three peaks and two valleys. Here’s how it looks: the middle peak towers above, while the two peaks on either side are at the same height. This pattern symbolizes a potential shift in market direction, making it a valuable tool for traders looking to capitalize on reversals.

One of the main attractions of the Quasimodo pattern is its high win rate. However, it’s important to note that this pattern is a rare gem in the trading world. Spotting one requires patience and persistence, which is why we recommend traders keep the QM Indicator running 24/5 to increase their chances. Using a VPS can be a smart move to ensure seamless, continuous monitoring. Don’t forget to turn on notifications to get alerts when a potential pattern emerges!

Quasimodo Indicator isn’t a standalone trading indicator System. Still, it can be very useful for your trading as additional chart analysis, to find trade exit position(TP/SL), and more. While traders of all experience levels can use this system, practicing trading on an MT4 demo account can be beneficial until you become consistent and confident enough to go live. You can open a real or demo trading account with most Forex brokers.

Understanding the Quasimodo Pattern

The Quasimodo pattern is named after the character from Victor Hugo’s “The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.” Just as Quasimodo has an asymmetrical appearance, this trading pattern reflects an imbalance in the market with its unique structure of three peaks and two valleys. This quirky pattern’s name highlights the need to spot unconventional opportunities in trading, much like Quasimodo’s character teaches us to see beyond the surface.

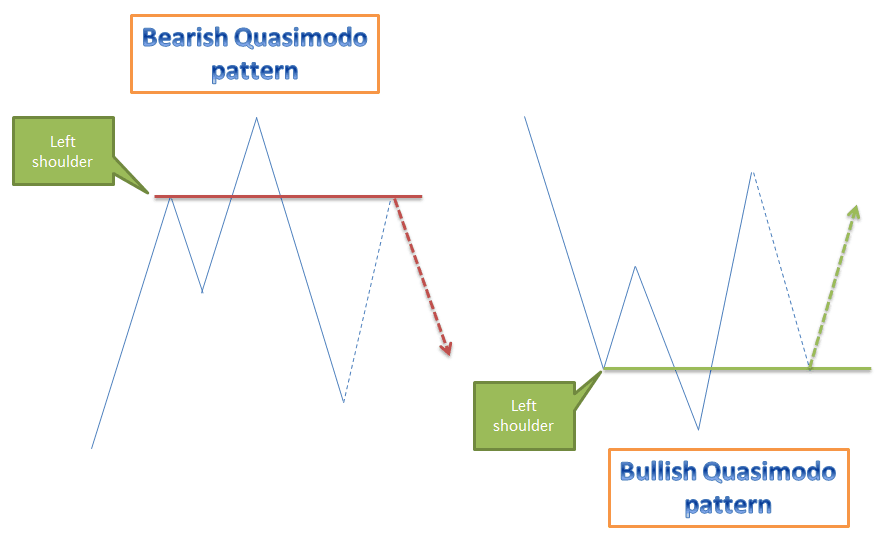

The pattern is easily recognizable once you know what to look for. It comprises three peaks and two valleys:

- Three Peaks: The standout feature is the middle peak, which is higher than its counterparts on either side. The two outer peaks sit at the same level.

- Two Valleys: Situated between the peaks, these valleys are key to understanding potential shifts in price direction.

This specific configuration indicates market indecision and often precedes a reversal, where the prior trend loses momentum and shifts direction.

Trader’s Benefit

Identifying the Quasimodo pattern can significantly enhance a trader’s ability to forecast market movements. Because the pattern suggests a reversal, traders who can spot it early may capitalize on the ensuing trend change. However, due to its rarity, implementing technology to monitor for its appearance can provide traders with a strategic edge.

Incorporating the Quasimodo pattern into your trading strategy contributes to a more robust system for deciphering market directions and making informed trading decisions. Understanding its formation and leveraging its indicators can help traders seize opportunities in both bullish and bearish markets.

Download a Collection of Indicators, Courses, and EA for FREE

How to use this Quasimodo Indicator

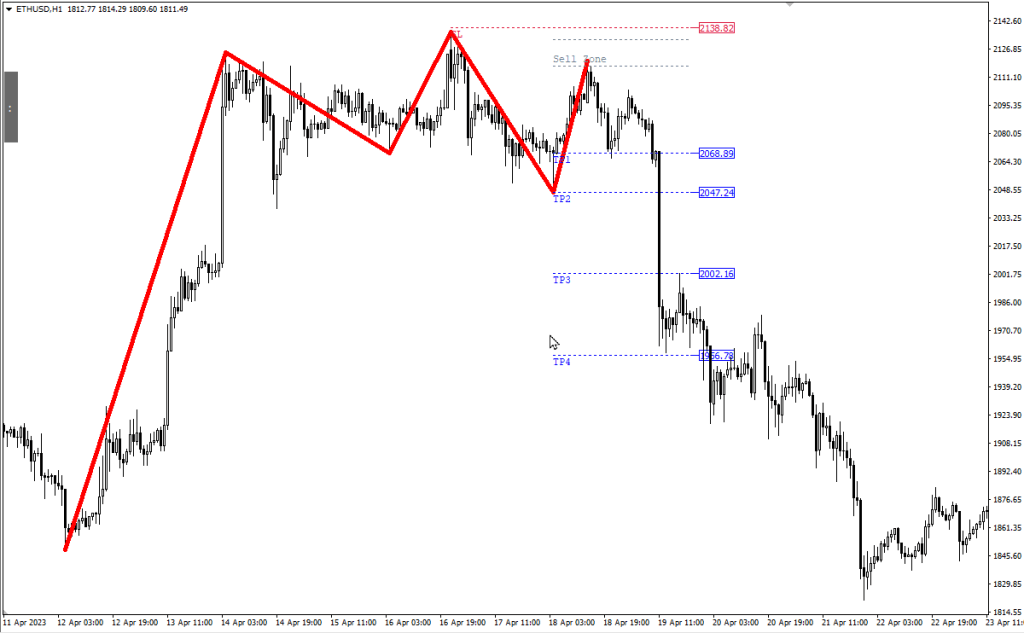

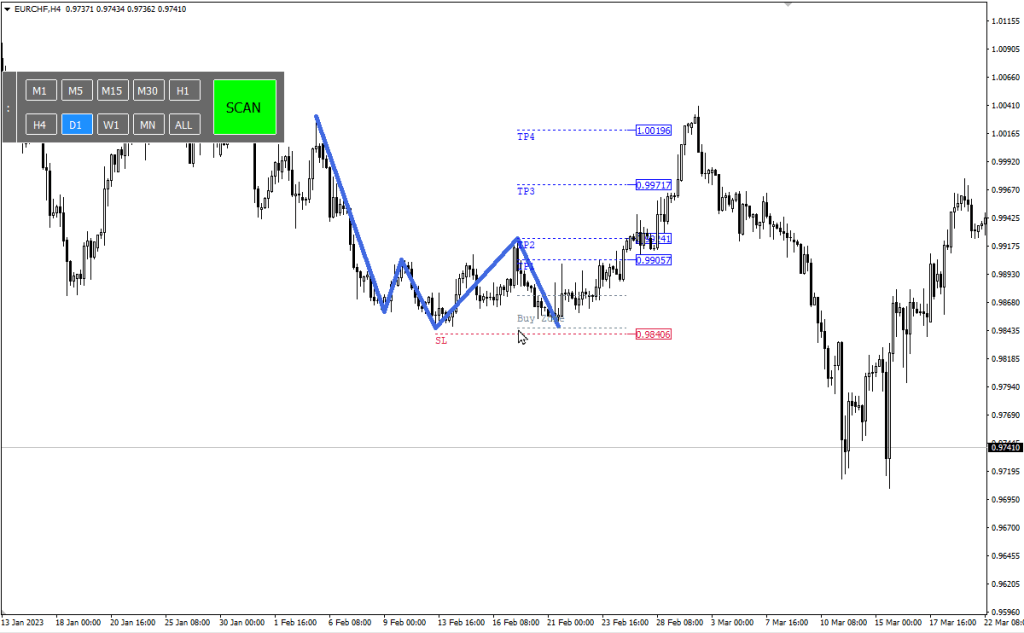

- Entry Point – To successfully trade using the Quasimodo Indicator, you need to wait for the price to retrace back to the “left shoulder” level. Think of this as the price pulling back to collect unfilled orders. That’s your cue to enter the trade. A helpful technique is to mark a supply and demand zone at this left shoulder level.

- Stop Loss – Protect your trade by setting a stop loss either above the higher high or below the lower low. This safety net ensures that your losses will be limited even if the market doesn’t move as anticipated.

- Take Profit – Your take profit level will vary depending on the type of reversal. Aim for the recent lower low for a bullish reversal and target the recent higher high for a bearish reversal. This strategy locks in your gains once the market hits these levels.

Conclusion QM Indicator

The Quasimodo pattern may not be the most common occurrence, but its potential benefits make it worth the wait. Traders can make the most of this pattern by utilizing technology and a strategic approach to entry and exit points. Whether you’re a seasoned trader or just starting, incorporating the QM Indicator into your toolbox can enhance your trading strategy significantly.